I woke up on Monday at my new Santa Fee accomodations, a charmingly kitschy motel that was highly recommended by my guidebook, The Silver Saddle Motel. In addition to being the only affordable option in the book’s section on Santa Fe, it was less than a mile walk to my rental car pick  up and offered a very generous continental breakfast. I stopped for a few snaps on my way out of the parking lot.

up and offered a very generous continental breakfast. I stopped for a few snaps on my way out of the parking lot.

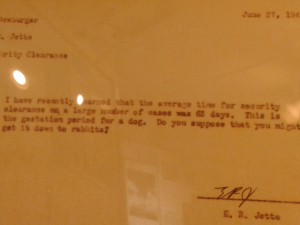

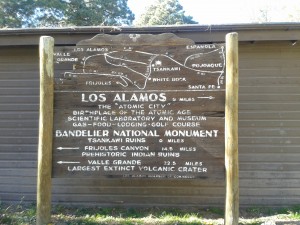

I headed north from Santa Fe to take in the High Road to Taos, but decided to stop at Los Alamos along the way, and hoped to get a hike at Bandolier National Monument. Los Alamos is a great place for a short visit because the tourist sites are easy to find and near each other. Equipped with a map from the Visitors Center, I walked over to the site of the former Ranch School, which was commandeered for use by the War Department when it began to explore the feasibility of creating a nuclear weapon. The school, which existed from 1917, was summarily closed down in February 1943, and the government amassed a camp there. Oppenheimer, Fermi, and other world class scientists took over the staff housing, and began developing the atom bomb. After a test in the desert in July 1945, the US deployed it twice against Japan in August 1945, which resulted in their surrender in September 1945. I went first to the historic museum, which places the Manhattan Project in the larger context of the area’s history. There are exhibits on the school, and on the culture of local people, for example. Of course, it also includes a number of items from the Mahattan Project, such as this letter griping about the slowness of individuals obtaining a security clearance.

I headed north from Santa Fe to take in the High Road to Taos, but decided to stop at Los Alamos along the way, and hoped to get a hike at Bandolier National Monument. Los Alamos is a great place for a short visit because the tourist sites are easy to find and near each other. Equipped with a map from the Visitors Center, I walked over to the site of the former Ranch School, which was commandeered for use by the War Department when it began to explore the feasibility of creating a nuclear weapon. The school, which existed from 1917, was summarily closed down in February 1943, and the government amassed a camp there. Oppenheimer, Fermi, and other world class scientists took over the staff housing, and began developing the atom bomb. After a test in the desert in July 1945, the US deployed it twice against Japan in August 1945, which resulted in their surrender in September 1945. I went first to the historic museum, which places the Manhattan Project in the larger context of the area’s history. There are exhibits on the school, and on the culture of local people, for example. Of course, it also includes a number of items from the Mahattan Project, such as this letter griping about the slowness of individuals obtaining a security clearance.

One of the most moving elements of the museum comes after the discussion of the rush to develop the atom bomb and the tests in the desert. In a small alcove, the museum displays large aerial photographs of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in October 1945, some two months after the weapons were used. The cities are in ruins. There has been much made about the morality of the US using these weapons on civilian populations to end World War II. The Bradbury Museum, which is affiliated with the National Laboratory at Los Alamos, discusses this in its presentation of the history. To me, it is a complex question, and one in which people often look at the decision ahistorically, as if the Japanese defeat and surrender was inevitable and would somehow have occurred without mass casualties. I had two uncles who fought at Okinawa, and my then 18 year old father was about to get on a Navy carrier to Japan. So I can’t look at the morality of the decision in a vacuum. However, it is also easy–particularly in a place like Los Alamos–to forget the utter devastation of what was developed there.

One of the most moving elements of the museum comes after the discussion of the rush to develop the atom bomb and the tests in the desert. In a small alcove, the museum displays large aerial photographs of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in October 1945, some two months after the weapons were used. The cities are in ruins. There has been much made about the morality of the US using these weapons on civilian populations to end World War II. The Bradbury Museum, which is affiliated with the National Laboratory at Los Alamos, discusses this in its presentation of the history. To me, it is a complex question, and one in which people often look at the decision ahistorically, as if the Japanese defeat and surrender was inevitable and would somehow have occurred without mass casualties. I had two uncles who fought at Okinawa, and my then 18 year old father was about to get on a Navy carrier to Japan. So I can’t look at the morality of the decision in a vacuum. However, it is also easy–particularly in a place like Los Alamos–to forget the utter devastation of what was developed there.  The atomic age has become the stuff of nostalgia, a simpler America, one certain of victory through discovery and hard work. In the midst of the kudos and nostalgia, it was great to see a reminder of what the bomb wrought. I am grateful to the museum for offering it. Oppenheimer, we are told, responded to the successful test of his work in the desert with a quote from the Bhagavad Gita: “I am become death, the destroyer of worlds.” In this case, discovery is a complicated legacy.

The atomic age has become the stuff of nostalgia, a simpler America, one certain of victory through discovery and hard work. In the midst of the kudos and nostalgia, it was great to see a reminder of what the bomb wrought. I am grateful to the museum for offering it. Oppenheimer, we are told, responded to the successful test of his work in the desert with a quote from the Bhagavad Gita: “I am become death, the destroyer of worlds.” In this case, discovery is a complicated legacy.

I headed out from the museum to Bathtub Row, so named because in the fast construction of military barracks that surrounded the building of the bomb before Germany could, these were the only houses  to have bathtubs. They housed the scientists, and are now, surprisingly, privately owned. I headed back to the Bradbury Science Museum then, which focuses on the world of science and the benefits it brings to human existence: vaccines, space exploration, alternative energy, etc. My time was short, so I took in the historical pieces of the museum, and a film extolling the work of the National Laboratories, before heading out on the High Road to Taos. The woman at the historical museum had advised that there was a truck jackknifed on the road leading to Bandolier, so getting there was going to be problematic. I decided to move it to later in the trip and headed for Chimayo.

to have bathtubs. They housed the scientists, and are now, surprisingly, privately owned. I headed back to the Bradbury Science Museum then, which focuses on the world of science and the benefits it brings to human existence: vaccines, space exploration, alternative energy, etc. My time was short, so I took in the historical pieces of the museum, and a film extolling the work of the National Laboratories, before heading out on the High Road to Taos. The woman at the historical museum had advised that there was a truck jackknifed on the road leading to Bandolier, so getting there was going to be problematic. I decided to move it to later in the trip and headed for Chimayo.

My trip to Chimayo was not long, but it was beautiful. It also moved me in in a dramatic fashion–in the way travel does–from the world of science to the world of

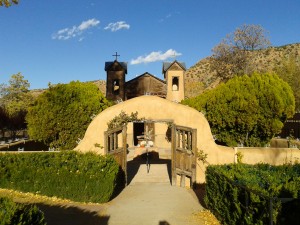

My trip to Chimayo was not long, but it was beautiful. It also moved me in in a dramatic fashion–in the way travel does–from the world of science to the world of  folk belief. My next stop was the Santuario de Chimayo, a set of chapels devoted to miraculous cures and pilgrimage set on the High Road to Taos. The site contains a number of charming adobe structures. The

folk belief. My next stop was the Santuario de Chimayo, a set of chapels devoted to miraculous cures and pilgrimage set on the High Road to Taos. The site contains a number of charming adobe structures. The  primary church, the Santuario, was built in 1816 on the site where a local man, Don Bernardo, discovered a cross bathed in a strange glowing light in 1810. It was twice removed to a nearby church at Santa Cruz only to reappear on the spot, so the Santuario was built to house it, and one can obtain holy dirt from the site. Pilgrims come to the spot seeking healing, and walls of

primary church, the Santuario, was built in 1816 on the site where a local man, Don Bernardo, discovered a cross bathed in a strange glowing light in 1810. It was twice removed to a nearby church at Santa Cruz only to reappear on the spot, so the Santuario was built to house it, and one can obtain holy dirt from the site. Pilgrims come to the spot seeking healing, and walls of

photographs and crutches left behind attest to the devotion many have for the place. The site enforces a strict policy of no photography inside the chapels and bookstores in order to protect the older buildings and artifacts. This is largely enforced on a honor system, but since there are constant reminders, I observed it. There is a second chapel there, this one dedicated to Santo Nino de Atocha, and image of the Christ Child. This shrine aims more at children. The story behind it is that the holy child spends his nights going around the countryside offering comfort to the poor and, in doing so, wears out his shoes. As a result, pilgrims bring children’s shoes as an offering. On every available surface, small

The site enforces a strict policy of no photography inside the chapels and bookstores in order to protect the older buildings and artifacts. This is largely enforced on a honor system, but since there are constant reminders, I observed it. There is a second chapel there, this one dedicated to Santo Nino de Atocha, and image of the Christ Child. This shrine aims more at children. The story behind it is that the holy child spends his nights going around the countryside offering comfort to the poor and, in doing so, wears out his shoes. As a result, pilgrims bring children’s shoes as an offering. On every available surface, small  shoes proliferate. As compelling as they were, I observed the command not to photograph in the chapels. The site, however, contains a few prayer portals, which appear to be newer structures where pilgrims can gather which also contain these offerings. They do not have signage prohibiting photography, so I snapped a statue of a pregnant St. Anne, the mother of Mary, with a wall of shoes beside her.

shoes proliferate. As compelling as they were, I observed the command not to photograph in the chapels. The site, however, contains a few prayer portals, which appear to be newer structures where pilgrims can gather which also contain these offerings. They do not have signage prohibiting photography, so I snapped a statue of a pregnant St. Anne, the mother of Mary, with a wall of shoes beside her.

The largest contingent of pilgrims come for Good Friday services in the spring, but there were a collection of tourists and pilgrims at the Santuario when I visited. In addition to the chapels, the site contains three gift shops and a number of monuments. After careful consideration, I purchased a locally made Nativity set and then headed back out onto the grounds.

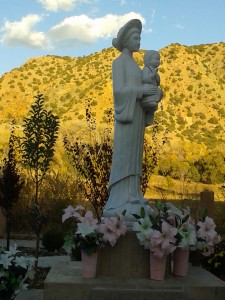

Statuary includes small children in line to see the Nativity, and a

Statuary includes small children in line to see the Nativity, and a

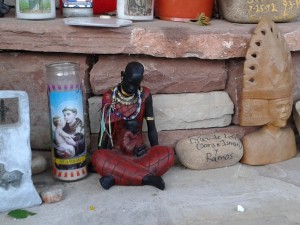

Vietnamese Madonna and child, donated by a local family. I was disappointed that there was no further explanation of this particularly lovely statue, which is an outlier among the largely Hispanic iconography of the rest of the site. Pilgrims leave behind offerings, largely in the form of votive candles and  rosary beads, which along with the photos offers a sense of the meaning of the place.

rosary beads, which along with the photos offers a sense of the meaning of the place.

On my way out, I stopped to speak with a woman who had come in from Albuquerque for her birthday. She tries to come every season because of the peace of the place, and today was her fall visit. She was delighted to share it with me.

On my way out, I stopped to speak with a woman who had come in from Albuquerque for her birthday. She tries to come every season because of the peace of the place, and today was her fall visit. She was delighted to share it with me.

The daylight was beginning to fade as I left. At the motel that morning, the clerk had helpfully noted to me that Chimayo and Espanola are the heroin capitals of  the US, so locals tend to be skeptical and visitors should exercise caution. I hoped to see some of the Chimayo weaving before I left. When I arrived at the crossroads that is the center of Chimayo, I stopped at the Ortega’s Weaving Shop. My phone battery was fading at this point, and the Chimayo Museum was closed on Monday (like the Louvre and other fine museums, I thought). The shop and nearby gallery were closing down, so I made a pass through and headed up the High Road. It is said to be beautiful, but the sun was setting as I drove the back roads, so I could make no more stops.

the US, so locals tend to be skeptical and visitors should exercise caution. I hoped to see some of the Chimayo weaving before I left. When I arrived at the crossroads that is the center of Chimayo, I stopped at the Ortega’s Weaving Shop. My phone battery was fading at this point, and the Chimayo Museum was closed on Monday (like the Louvre and other fine museums, I thought). The shop and nearby gallery were closing down, so I made a pass through and headed up the High Road. It is said to be beautiful, but the sun was setting as I drove the back roads, so I could make no more stops.

I arrived at my home for the night, the Taos Inn, thinking that the day could not have been more perfect. I had traveled the world of science and devotion, and was staying at a historic inn in the off season, so the price was affordable. A local band was setting up in the lobby, and I enjoyed dinner at Doc Martins, the attached restaurant. I learned upon arrival that the hotel offered access to a local health club with a lap pool, so I headed out for my first swim in a week. It was slow going at first, as I struggled to breath in enough oxygen at this altitude while I lapped in the largely abandoned pool. But I pushed forward and completed my laps before heading home to the hotel for the night.