I had wanted to get to Emmitsburg to see the site of St. Elizabeth Bayley Seton’s shrine since I started planning my time in Maryland, but the site was largely closed until this point in my journey. She had been canonized during the USA bicentennial in my childhood, so I heard a lot about her, but confess I knew very little. I finally broke away to the shrine after a morning of work, and arrived back in mountainous Maryland in the beautiful National Shrine of St. Elizabeth Ann Seton in Emmitsburg. Despite Seton’s importance as the first person born in North America to be canonized a saint, the shrine felt very simple and reflected the atmosphere of most provincial headquarters for religious orders I have known in US Catholic life. Seton’s story combines the ordinary with the providential in interesting ways. Born just after the American Revolution, she was raised in a prominent New York Episcopalian family. Her father was a doctor who served the indigent and her mother and little sister died when Elizabeth was young, leaving an impression on her. In her late teens, she married married William Seton and they enjoyed a loving, happy, and prosperous marriage. He was a merchant trader and they counted Alexander Hamilton and George Washington among their friends and guests.

She was a devout and prosperous woman with five children when her husband had a financial setback that brought them near bankruptcy. They decided to take some time in Italy so that he could heal from tuberculosis, which afflicted his family. They had come from New York, which had an outbreak of yellow fever, so they were quarantined upon arrival in Italy for 30 days. The house where they quarantined exacerbated William’s tuberculosis and he died 10 days after their release. Grief stricken, she and her daughter Annamaria stayed with their family friends there for five months and Elizabeth became enamored of their daily participation in daily Eucharist. As an Episcopalian, she could not receive communion, but the near presence of Christ comforted her. When she returned to the US, she expressed a desire to convert to Roman Catholicism, but was warned away from it because her socially-prominent friends warned her that it was the religion of dirty Irish immigrants and not acceptable. Even local Catholic leaders cautioned her about the social ostracism she would face, but she desired the Eucharist so much that she converted.

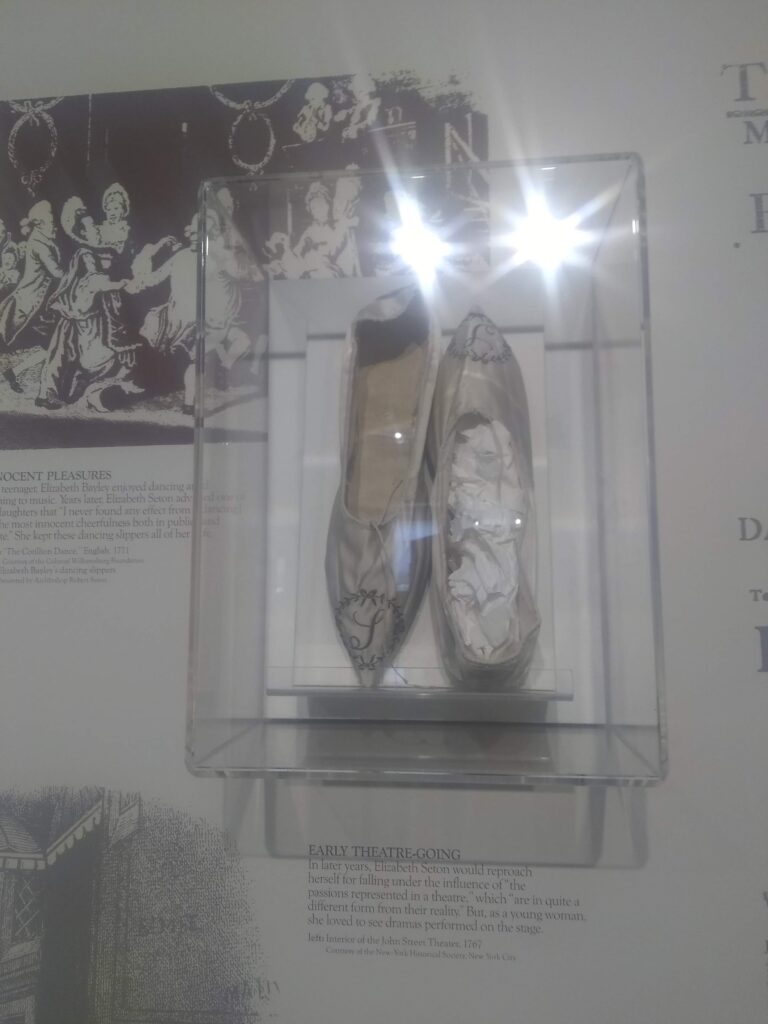

This complicated her efforts to start a school and earn a living for her family in New York because she had no affluent young women who would attend her school. So she wrote to the Archbishop of Baltimore, a state that had a history of Catholic settlement, and he welcomed her. Her first school in the city operated across class lines, and one of her affluent families bought land for her in Emmitsburg. She and a company of like-minded women, her children, two sisters-in-law and a few Bayley cousins, moved there together to establish a school, St. Joseph’s Academy and Free School. The site speaks less about the foundation of the order than it does their ministry of education, which became the origin of parochial education in the US. In time, they established religions community there, the Daughters of Charity. Two of her daughters died at Emmitsburg before her and one outlived her. One son had a career in the US Navy and established a family that continued into the 1960’s; another died while doing service work in Africa. Her youngest daughter joined a separate order in middle age and worked in New York for the rest of her life. The site included a basilica and I arrived at the end of Mass, having elected to take the tour in my rush to get back home that afternoon. It was a peaceful and beautiful site, and the museum contained an excellent explanation for the canonization process, designed to explain it to non-Catholics, but educational to us as well.

My rush to leave was pointless–traffic was congested and prevented me from getting to the appointment I had planned, so I cancelled. I took the opportunity to see another beautiful site, Catoctin Mountain Park, a part of which includes Camp David. That was not open for visitors, but the park had a ranger and small, outside welcome table that included maps. I was not prepared for a hike, but took three small walks in the hundred-degree heat as well as I could in my Birkenstocks. I saw some beautiful views and a Prohibition-era distillery site.

I could not head home without a stop at Catoctin Breeze Winery, which had just reopened in a restricted way. They could not offer a tasting, but their menu of fruited meads was compelling so I took the recommendations of the college kids working there and headed home with a bottle through covered bridges and thwarted attempts to visit a local distillery. This trek up to the northern part of the state had been an abundant one, despite the heat and my limited plans. I hope to return, if for no other reason than the fantastic mead.