I woke up in Houma on Ash Wednesday, which doubled that year as Valentine’s Day. I moved at a leisurely pace, determined to be restful after the go-go-go of New Orleans Mardi Gras. I had no guide book, so I was depending on the internet to help me choose the sites to see. I tried to take in a few recommended attractions in Houma but they were closed. It was unclear whether that was a permanent condition or if I just was getting too early of a start on the day after Mardi Gras season ended. Whenever I spoke to somebody in New Orleans about seeing the whole state (not just their city), they would tell me to go see the plantations. So I headed out to the Great River Road (something I have also driven in Iowa further up the same river) to visit two plantations in Vacherie. I figured, if I could find it along the way, I’d stop off for church and some ashes. My timing turned out to be terrible and I missed Mass in a succession of small towns. I finally found my pilgrim way to Vacherie.

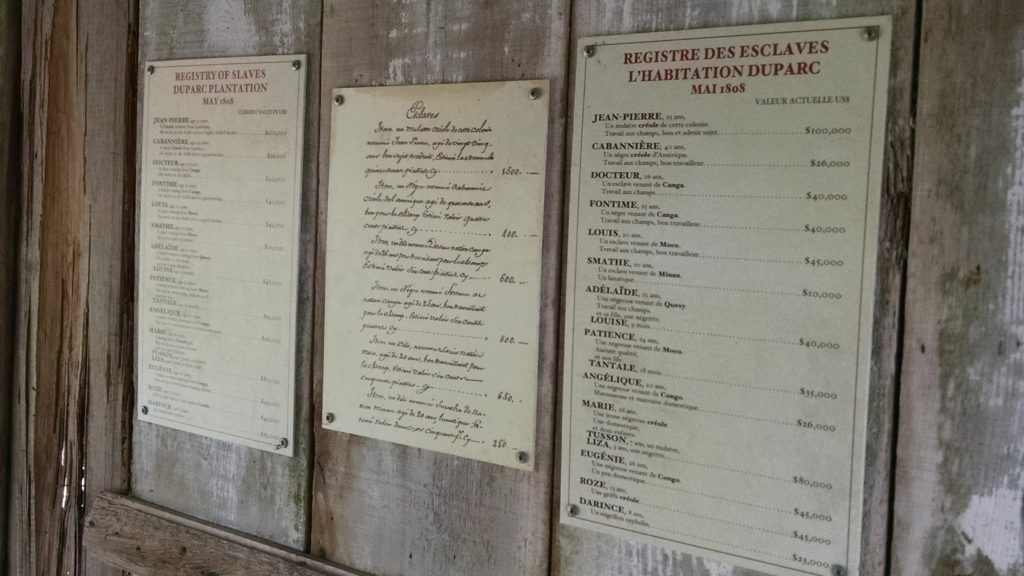

My first stop was Laura Plantation, a creole plantation on the west bank of the Mississippi. Throughout my odyssey around the US, I have missed the chance to visit a number of plantations, whether because I arrived on the day they were closed, or they are a bed and breakfast now and offer no tours. I believe this was my first tour of one that was trying to tell that story, and this plantation sets the bar high. This site had originally been known as the DuParc Plantation for the founding family, which had received the land in an 1804 grant from Thomas Jefferson for services in the American Revolution. It produced sugar, and later indigo, rice and pecans, using enslaved labor. In the 1870’s, a folklorist named Alcee Fortier collected and published Senegalese stories in Louisiana Creole from the freedmen living there, and some of them (like the Brer Rabbit and Brer Fox tales) became famous, which drew in preservation money in the late 20th century when the plantation moved out of private ownership.

The plantation does an compelling job telling the story of the generations of the French/American/creole family that lived there until 1891, the enslaved people and sharecroppers who labored there throughout its history, and the fate of the area economically both before and after the Civil War. Women had a prominent role in running this plantation, and the final DuParc family owner–Laura Locoul Gore–even produced a memoir of her life and family there that is highly readable. The staff deal with the history very directly, and their efforts to recover and tell the individual stories of the enslaved people there is quite detailed. They even provide information about the difficulties of trying to trace historical information on the farm laborers. The site also offers an extensive bookstore.

Not far away is another plantation, Oak Alley, which is closer to what one would imagine a plantation visit to be. The grounds feature the big house which can be used for special events and as an inn. The tour was less grounded in the plantation’s people, but the structures–both of the mansion and the outbuildings for enslaved labor and other agricultural production–are well preserved. If Laura offered an artisanal approach to the plantation history along the Mississippi, Oak Alley was more corporate. This property had endured more change, both in owners and in agricultural aims, than the Laura Plantation and moved into public hands in 1972. It was certainly more popular of an attraction, and I wandered the extensive grounds in the bright sun with a wider variety of folk than at Laura.

Still, each one told of a similar historic trajectory. Early days in the 19th century of great wealth in sugar, then devastation with the Civil War, then efforts to build again using sharecropping labor that tied poor laborers to the land, inventiveness to keep the various large farms together despite splintering family trees, and a struggle with poverty. As I drove through Louisiana that evening, I could see a number of poor communities in the area, homes built of mud and corrugated iron, where trailers were the more affluent accommodation. According to the tour guides, two hundred years before, the owners of this land were some of the wealthiest in the world. The period since the Civil War dwarfs the antebellum period by decades, but pervasive and long-standing poverty remains clear, both in the stories and in the sites.

I made my way to St. Francisville, where I hoped to spend the night in one of its reputedly charming bed and breakfasts. As I called to make reservations, I was reminded that the day was Valentines Day, and my late planning had put me at a disadvantage. There was no rooms to be had in that sector of accommodation. True to form, I arrived at one of the local churches as Mass was letting out, but one of the friendly congregants dragged her thumb across her ashes and traced a cross on my forehead with a little blessing. I needed it, as the night was getting late and dark and accommodation was scarce.

I finally found an opening at The Village Hotel, a seemingly close ten miles away. I drove around bayou country in the dark night feeling more and more fatigued and concerned about being lost in the pervasive darkness. I tried to talk some sense into myself but, when I stopped at a redlight at the corner of two very isolated streets, there was a sign warning me that Dixon Correctional Prison was nearby and I should not pick up hitchhikers. After a few missed turns, I arrived to a place that looked like a crab shack, and stopped for directions. Turns out I had arrived, and they showed me to my room on the top floor.

By this point, everything seemed sinister: the Madonna and child on the wall had eyes that followed me everywhere, the closet contained pictures of a early 20th century bride, which made me feel haunted. Once I got internet access, I learned that the place is haunted and I weighed up whether the second floor was a better or worse bet than the first, or my car. The staff member I encountered did not commit to whether there would be breakfast in the morning, and I wondered if that was because I would not be alive to see it. But I was in the inky darkness of rural Louisiana on Valentines night, so I had limited options at that point. I laid in bed tracing the torturous twists and turns in my love life that had led me to be spending Valentines night alone near a Louisiana prison in a haunted inn where nobody would hear me scream and my cell phone was mostly dead.

I hoped it would not end this way, but at least I got to see Mardi Gras.