My last day in Indiana began in the town I had been most eager to see, Columbus. The town, like Goshen and Valparaiso, is a relatively small Midwestern town. What makes it remarkable is its collection of architecture. In the era following World War II, the town invested in modernist architecture and, in doing so, became a center for building and landscape design. Although it is not far away from places I had lived, and I had long wanted to see it, I never had the opportunity to visit there before.

I headed over to the visitor center, where I sat the orientation video and purchased two guides for visiting the city. According to the video, what put Columbus on this unique path was largely the vision of J. Irwin Miller, scion of a prominent Columbus family, who inherited the nearly bankrupt family business, Cummins, Inc., during the Depression. He was young and implemented changes that eventually made the business profitable. However, just as it was in the black, World War II broke out and he enlisted, leaving the business in the hands of an uncle, who later passed away. Because Cummins produced diesel engines, a priority in the manufacture of tanks and military vehicles, Miller was released from service and returned home to Columbus to run the business in wartime.

Once there, he was instrumental in inducing Eliel Saarinen to build the new First Christian Church in Columbus. It was innovative design, considered at the time one of the nation’s most unique churches.  After the war, as veterans returned and Columbus boomed, the town needed build schools to accommodate the surge. Irwin argued that good, innovative design would be better for the city. Mediocrity, he argued, is more expensive than excellence because it results in rebuilding. He proposed an innovative private-public partnership. If the city leaders chose an architect off a short list he provided, his company’s foundation would pay the fees, and the city would pay the cost of building. And so it began. Schools, libraries, the post office, churches, common spaces, city hall, even the parking garage, are all designed by masters. There’s too many buildings for me to post everything here. After considering all my options at the visitor’s center, I purchased two items to aid Tamu and me in a walking tour: a set of cards with a cell phone number to call offering background on eleven items of public art or architecture, and a walking map highlighting 78 items of interest.

After the war, as veterans returned and Columbus boomed, the town needed build schools to accommodate the surge. Irwin argued that good, innovative design would be better for the city. Mediocrity, he argued, is more expensive than excellence because it results in rebuilding. He proposed an innovative private-public partnership. If the city leaders chose an architect off a short list he provided, his company’s foundation would pay the fees, and the city would pay the cost of building. And so it began. Schools, libraries, the post office, churches, common spaces, city hall, even the parking garage, are all designed by masters. There’s too many buildings for me to post everything here. After considering all my options at the visitor’s center, I purchased two items to aid Tamu and me in a walking tour: a set of cards with a cell phone number to call offering background on eleven items of public art or architecture, and a walking map highlighting 78 items of interest.

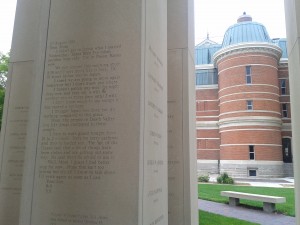

I’ll concentrate on my three favorite things. First was the Republic newspaper headquarters, a 1971 building designed by Myron Goldsmith. It has glass walls, because the paper, sitting across from city hall and the county courthouse, should represent transparency. Unbelievably, I took no photos of the building, probably because I could not do it justice compared to the photographs in the guides.  Second was the county Veterans Memorial, a 1997 design of architects Thompson and Rose and landscape architect Michael Van Valkenburgh. The memorial contains pillars with quotes from letters of those who were killed in action. You move around among the pillars reading the words of these men to mothers, fathers, and sweethearts at home, which are followed by details of where, when, and how they died. It was incredibly moving, yet simple and respectful. Third was the Chaos I sculpture of Jean Tinguely, which is ensconced inside the Commons, a 2011 building designed by Koetter Kim & Associates to protect this beloved public art from the elements that were causing decay. While I was inside circling the sculpture, the Hindu community was celebrating a Puja on the upper floor of the atrium. There was chanting and incense wafting through the air, while members of the public moved in and around this lovely work. The feeling was so remarkable that I took only digital film of it, and have no photos to post.

Second was the county Veterans Memorial, a 1997 design of architects Thompson and Rose and landscape architect Michael Van Valkenburgh. The memorial contains pillars with quotes from letters of those who were killed in action. You move around among the pillars reading the words of these men to mothers, fathers, and sweethearts at home, which are followed by details of where, when, and how they died. It was incredibly moving, yet simple and respectful. Third was the Chaos I sculpture of Jean Tinguely, which is ensconced inside the Commons, a 2011 building designed by Koetter Kim & Associates to protect this beloved public art from the elements that were causing decay. While I was inside circling the sculpture, the Hindu community was celebrating a Puja on the upper floor of the atrium. There was chanting and incense wafting through the air, while members of the public moved in and around this lovely work. The feeling was so remarkable that I took only digital film of it, and have no photos to post.

After my walk around town, I headed out to Mill Race Park, where Tamu–whose appreciation of architecture is not as sophisticated as one might assume–and I took a walk around the lake.  It had been an incredible day, inspiring even. Throughout the trip, I had been thinking on why some midwestern towns thrive and some decay. Columbus’ story makes the case that, in addition to industry, there needs to be people of vision and innovative solutions to financing. I come from Toledo, Ohio, a Rust Belt town, and for awhile I remember there being some discussion about the importance of attracting an educated class in addition to keeping the Jeep plant in the area for its jobs. The idea is that an educated class sets a vision into the future. After Columbus, I see the connection better than before.

It had been an incredible day, inspiring even. Throughout the trip, I had been thinking on why some midwestern towns thrive and some decay. Columbus’ story makes the case that, in addition to industry, there needs to be people of vision and innovative solutions to financing. I come from Toledo, Ohio, a Rust Belt town, and for awhile I remember there being some discussion about the importance of attracting an educated class in addition to keeping the Jeep plant in the area for its jobs. The idea is that an educated class sets a vision into the future. After Columbus, I see the connection better than before.

When we finished at the park, I decided to set aside my plan to have lunch in Indianapolis and stayed in the area. I happened upon Pacheco Winery, which is housed at a renovated service station within the city.  Because of the long drive in front of me, I did not indulge in any wine. However, the sliced beef sandwich was so remarkable that I did not miss the wine.

Because of the long drive in front of me, I did not indulge in any wine. However, the sliced beef sandwich was so remarkable that I did not miss the wine.

I could have stayed in Columbus all day, except I needed to get to Toledo by that night. I promised myself that, one day, I would get back to southern Indiana to see the Miller House and other sights. Then I headed north for Fort Wayne, which I had saved until the end because of its proximity to home.

As I dashed up the highway heading northwest, my attention was caught by a sign announcing the James Dean Museum, something I thought I had missed earlier in the week. Fairmount is the hometown of James Dean and, in addition to the museum, they host a annual festival every September. This may seem like a quirky, small thing. However, I know from personal experience that hotels around the area, including all the way to Muncie, fill up on this particular weekend to celebrate the life of one of Hollywood’s anti-heroes, whose life was cut short after only three memorable films.  The museum is housed in the town, but Dean grew up in a farm outside of town. The museum, which contains lots of 1950s-era paraphernalia, is not a structure of personal relevance to Dean. However, the proprietor was very helpful, and provided a map to sights of interest all around town. Since it was a beautiful day and I had time, I headed out to the graveyard, but was never successful in locating Dean’s individual marker. Since it is not a big place, I probably could have searched for a bit longer, but it occurred to me then that I am not an uber-fan or anything. I had stopped for the quirkiness, and had indulged in enough of that. I took a drive past his aunt’s farm, which remains in the family. It was prosperous looking, and I wondered how they handle the people who no doubt still come to visit them. I, however, was not one of them. I turned around and headed back to the interstate.

The museum is housed in the town, but Dean grew up in a farm outside of town. The museum, which contains lots of 1950s-era paraphernalia, is not a structure of personal relevance to Dean. However, the proprietor was very helpful, and provided a map to sights of interest all around town. Since it was a beautiful day and I had time, I headed out to the graveyard, but was never successful in locating Dean’s individual marker. Since it is not a big place, I probably could have searched for a bit longer, but it occurred to me then that I am not an uber-fan or anything. I had stopped for the quirkiness, and had indulged in enough of that. I took a drive past his aunt’s farm, which remains in the family. It was prosperous looking, and I wondered how they handle the people who no doubt still come to visit them. I, however, was not one of them. I turned around and headed back to the interstate.

My last stop in Indiana was Fort Wayne. I arrived in the evening, and my first stop was the Johnny Appleseed gravesite on the outskirts of town.  It took me a few tries to find it, but Tamu was happy to get there, as it sits in a lovely large park filled with apple and crabapple trees. Tamu wandered happily. I had no idea Johnny Appleseed was based in my home area, so this was a happy find.

It took me a few tries to find it, but Tamu was happy to get there, as it sits in a lovely large park filled with apple and crabapple trees. Tamu wandered happily. I had no idea Johnny Appleseed was based in my home area, so this was a happy find.

On my way out to the grave, I had passed a replica of the original fort for which the town is named, so I knew I was near the area where the St. Joseph and St. Mary Rivers converge to form the Maumee River, which then flows from Fort Wayne into Lake Erie at my hometown, Toledo. I had never been to the origin point of the river that was my neighbor, so I became determined to find it. The evening was fading toward night, and I had no clear directions. Finally, I turned into a park near where it seemed the St. Joseph must end, and I took a path inside. Nothing was marked, and it was impossible to find specific details online.  The path took me past the reconstructed fort. I let Tamu walk off leash, which I soon regretted because I lost him in the brush around the river. I nearly gave up on my quest to find the source of the Maumee, when I climbed onto a little footbridge. Standing on it, I realized that I had found it, the spot where the three rivers converge. I stopped for a minute and admired the site. Of course there were no directions or markers; this is a state where people don’t show off easily. I was just happy I found it before dark.

The path took me past the reconstructed fort. I let Tamu walk off leash, which I soon regretted because I lost him in the brush around the river. I nearly gave up on my quest to find the source of the Maumee, when I climbed onto a little footbridge. Standing on it, I realized that I had found it, the spot where the three rivers converge. I stopped for a minute and admired the site. Of course there were no directions or markers; this is a state where people don’t show off easily. I was just happy I found it before dark.

It was the perfect way to end my trip to Indiana. As darkness fell, I headed out on the highway that had been the Erie Canal, knowing that it would lead me home.